This Photograph : Reiner Blunck

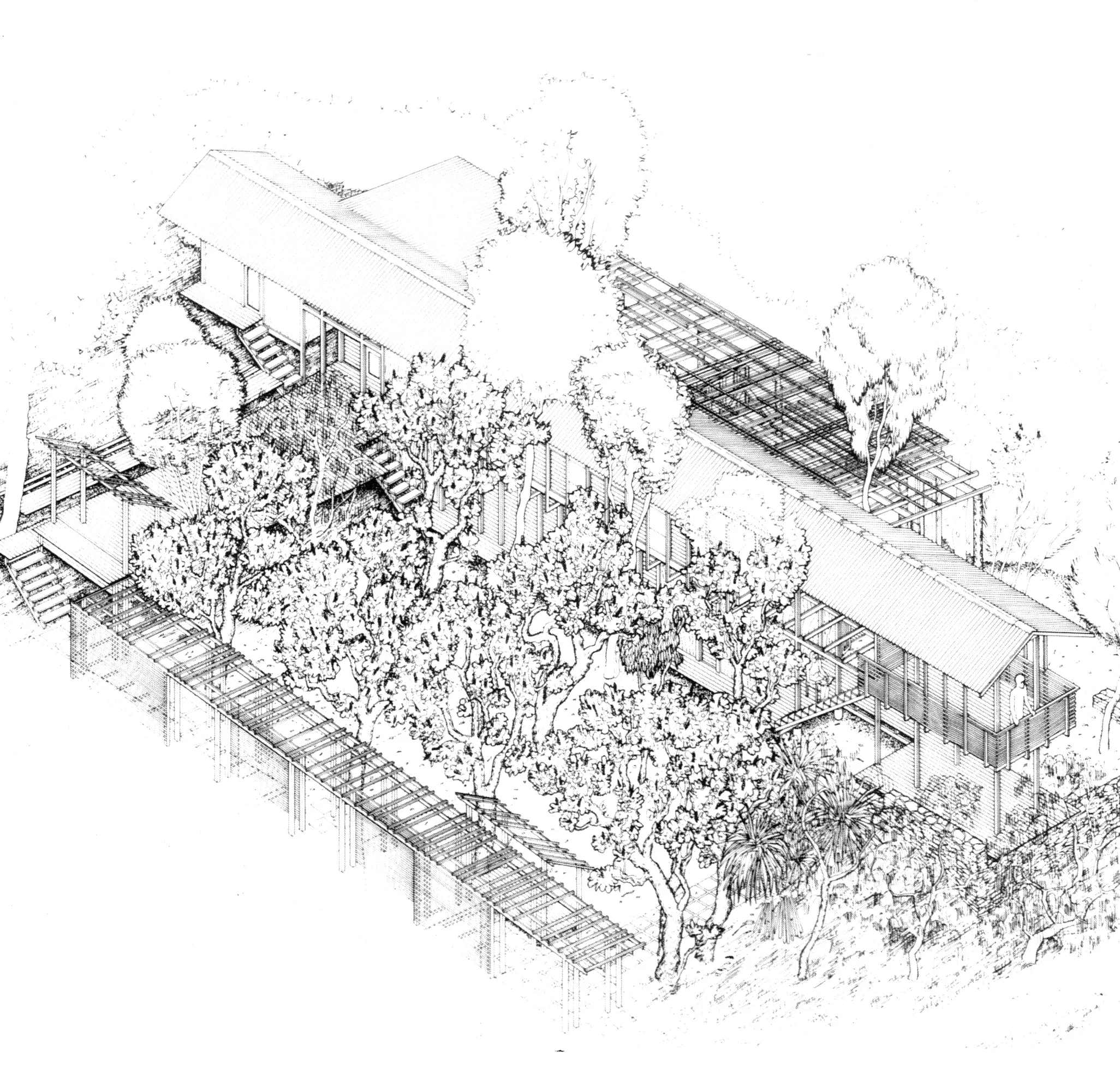

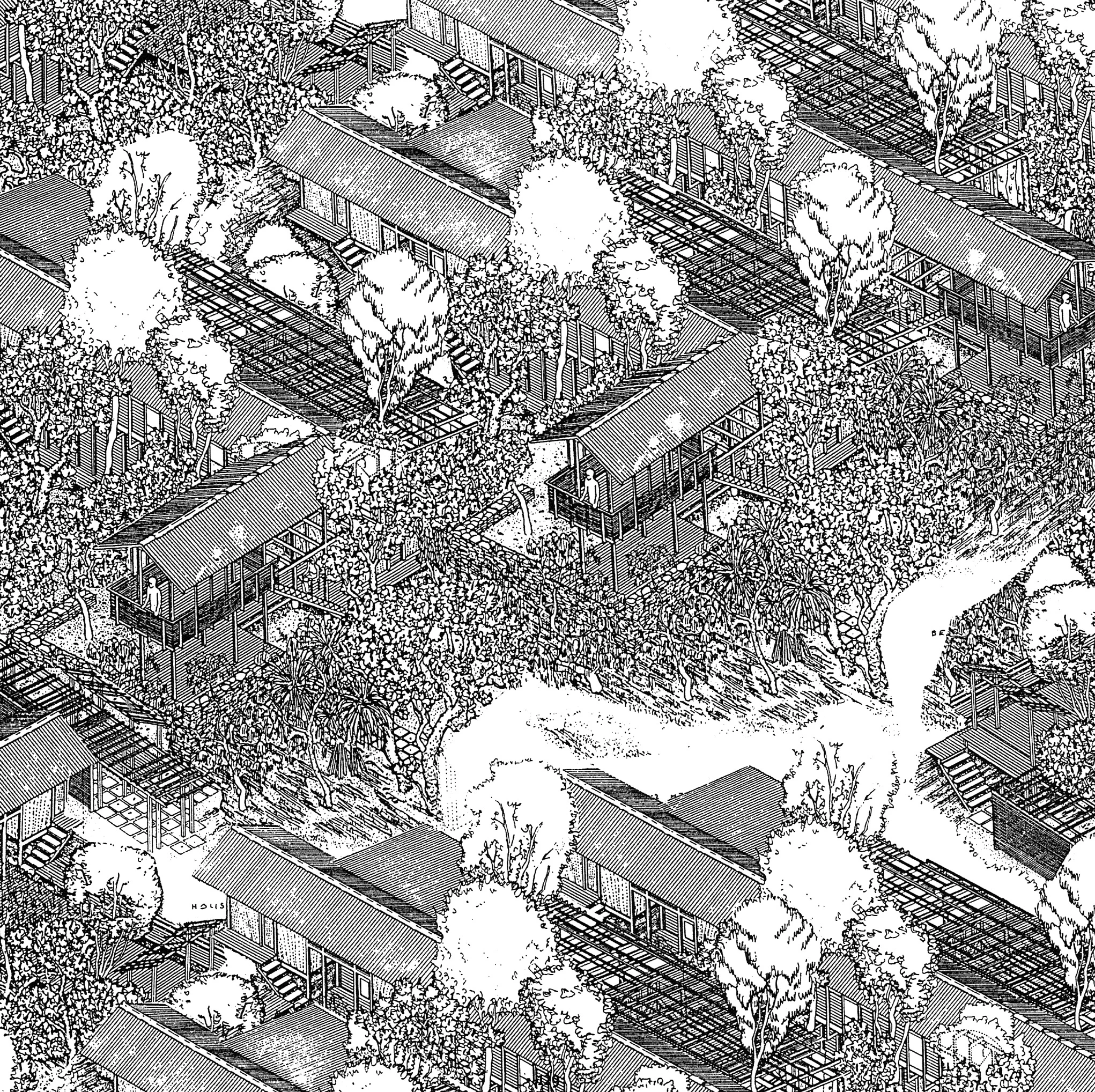

Mooloomba House, North Stradbroke Island, Queensland, Australia : 1995-99

The design has two primary intentions; to intensify the presence of landscape and to explore the expressive capacity of hardwood in terms of material properties, geometry and metaphor.

Hardwood has conventionally been incorporated within stud-framed systems to conceal the defective behavior of the frame including those well known characteristics of hardwoods to shrink, harden, warp, twist, cup and crack as they dry after milling. Sheeting over hardwood has always seemed to us an unfortunate loss of architectural opportunity in a material where high strength and durability does permit an external use and potential to contribute to building expression.

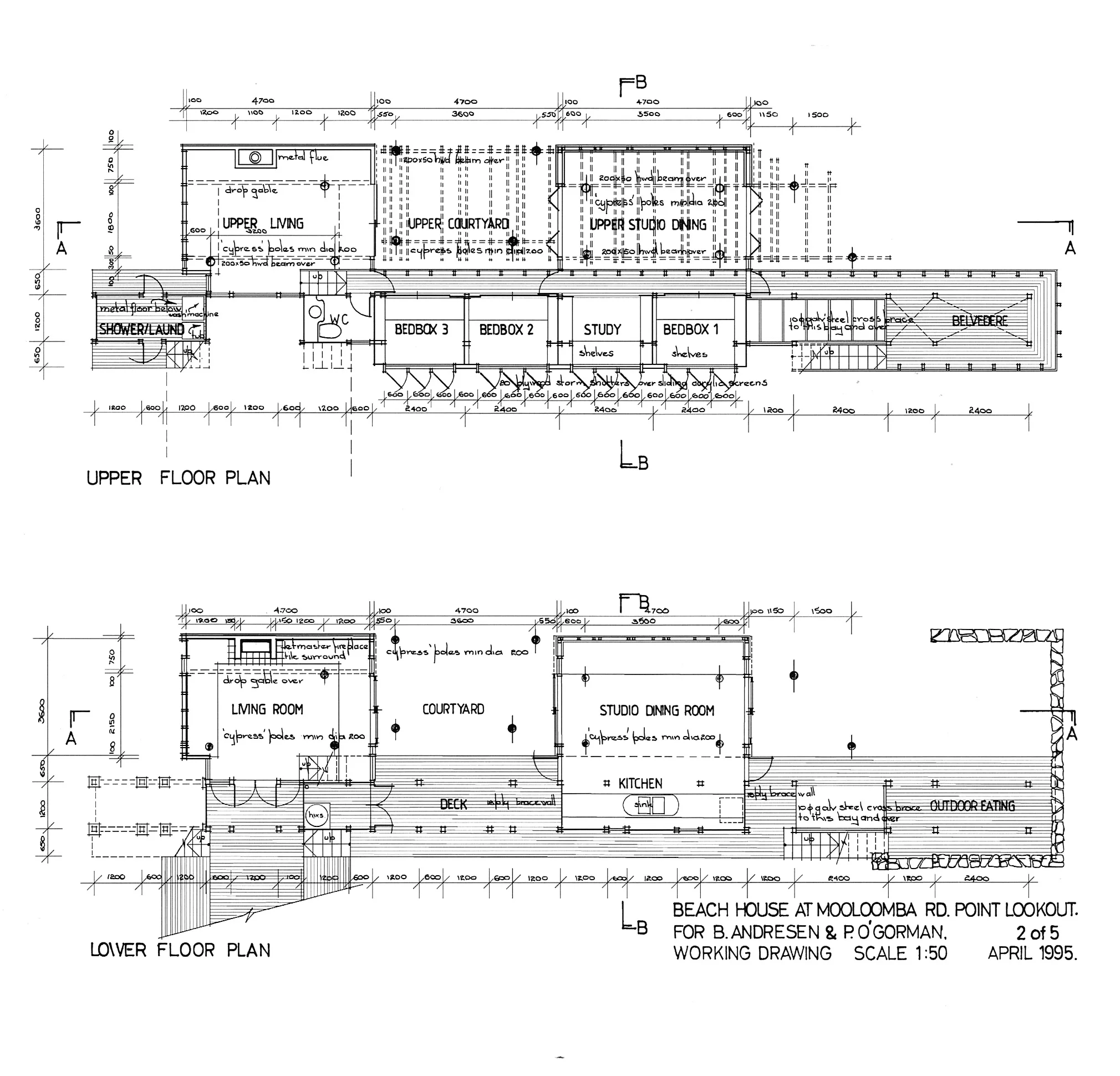

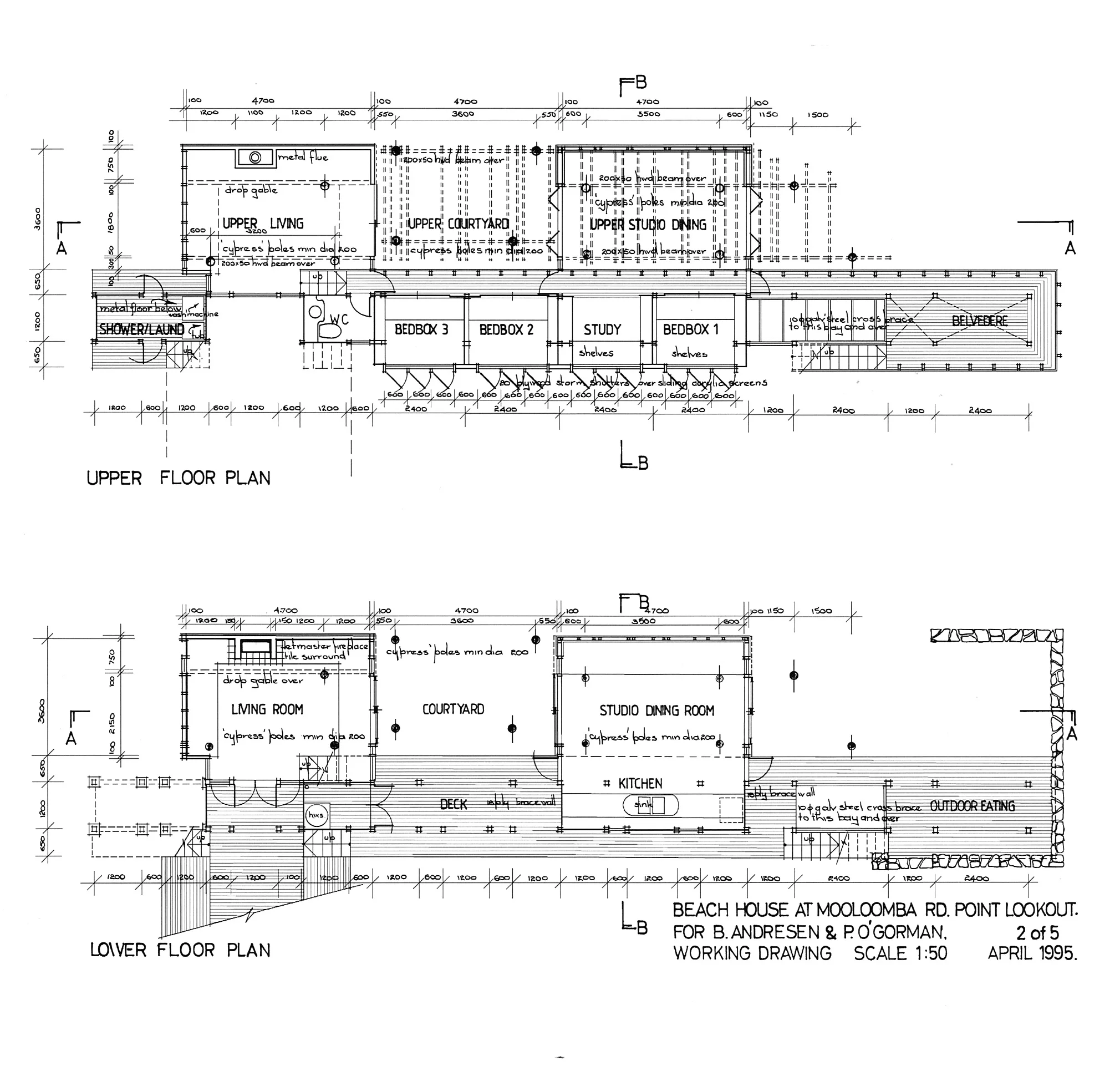

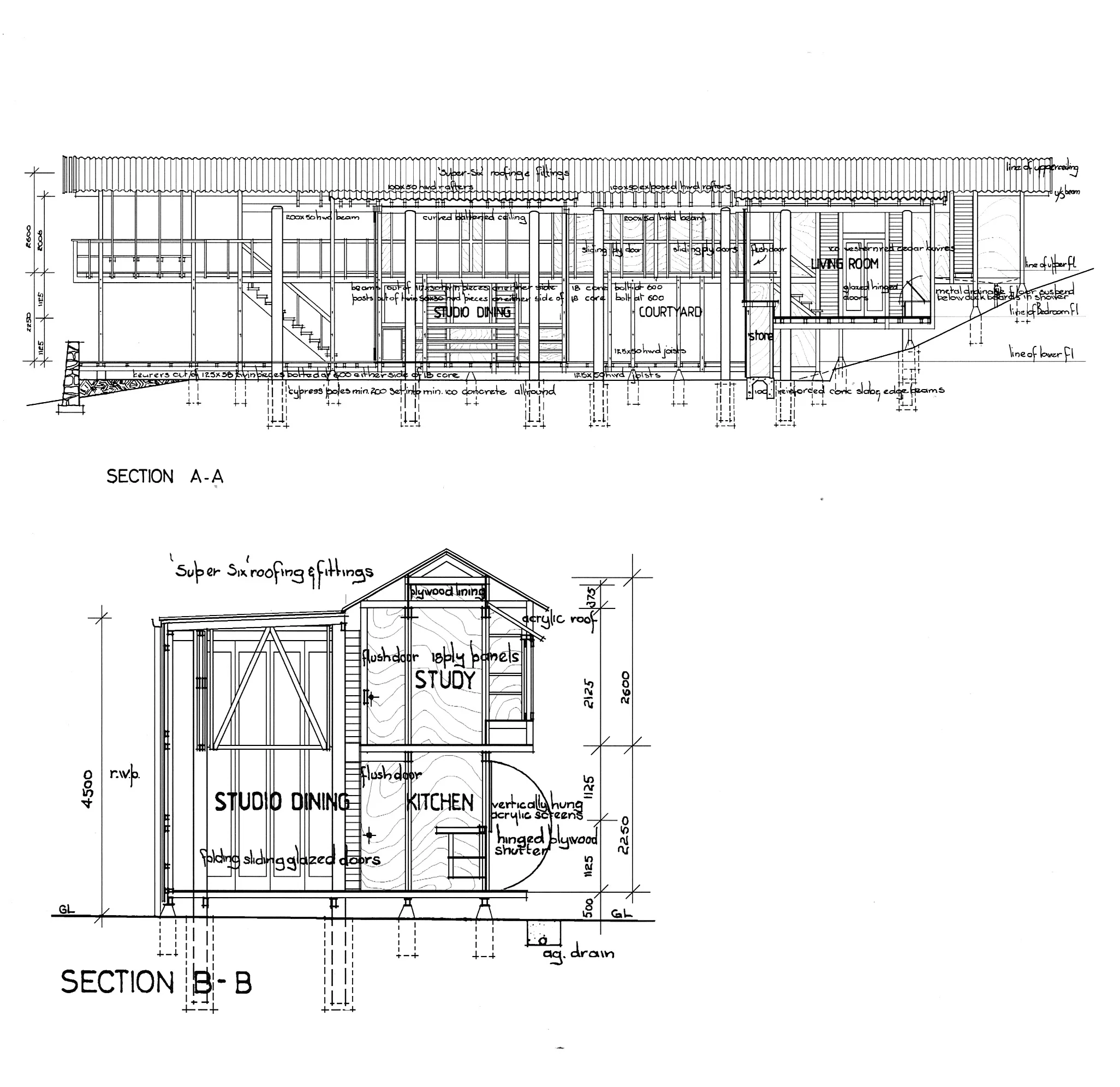

In Mooloomba House the simple strategy adopted, in order to tame excessive lateral movements, has been to vertically laminate thin, hardwood members of opposing grain formation and integrate a 1200mm by 2000mm wall panel of 18mm waterproof ply sheeting sandwiched between. The frame simultaneously forms enlarged 'cover battens' over the joints in sheets. This technique also facilitates a prefabrication process. Having drawn the hardwood frame into playing an expressive role in the building three key ideas inform the underlying architectural intent for constructing the house.

Firstly, before Homeric times the ancient Greek word for harmony, “harmonica”, was a term meaning the harmonious pattern of sounds, visuals, colours etc. as well as a term used in joinery or carpentry meaning "a timber frame such that to take away one piece would collapse it" – informing the idea that the components must fit together harmonically to make a whole. In Mooloomba House the generative 1200 x 2000 (1:1.618) proportion of the expressed wall panel and primary frame is intended to link the ancient meaning of harmony with the poetic interpretation of a mathematical proportioning system that offers visual integrity. In these days of environmental crisis the ancients' belief, that nature and the entire 'spherical' universe form a living harmonic, whole does not seem an inappropriate reference. To recognize the humble timber frame as the origin/genius of such a profound sequence of thought is to expose its architectural potential.

The second idea is that space may be characterized by constructional form. For example the open assemblage of relatively thin members can characterize a bower space such as the woven balustrade of the belvedere (“tectonic space”). Or the creation of a continuous surface, as if carved out of a mass, can characterize a cave space such as the lined corner of the room with the fireplace (“stereotomic space”). The thought in this small house was to explore the inclusion of these different constructional forms, all of hardwood, in three different segments of the building, to be held together in forms of what Aldo van Eyck called “reciprocity”.

The third idea, made possible by the benign climate of North Stradbroke Island, is the opportunity of creating space with 'transparencies’ inherent in tectonic form. Such opportunities begin to bridge technology (material and technique), territoriality (the plan), light, and relationship with the landscape, and, also offer an opportunity for what Colin Rowe termed “phenomenological transparency” where several conditions may be 'layered' together.

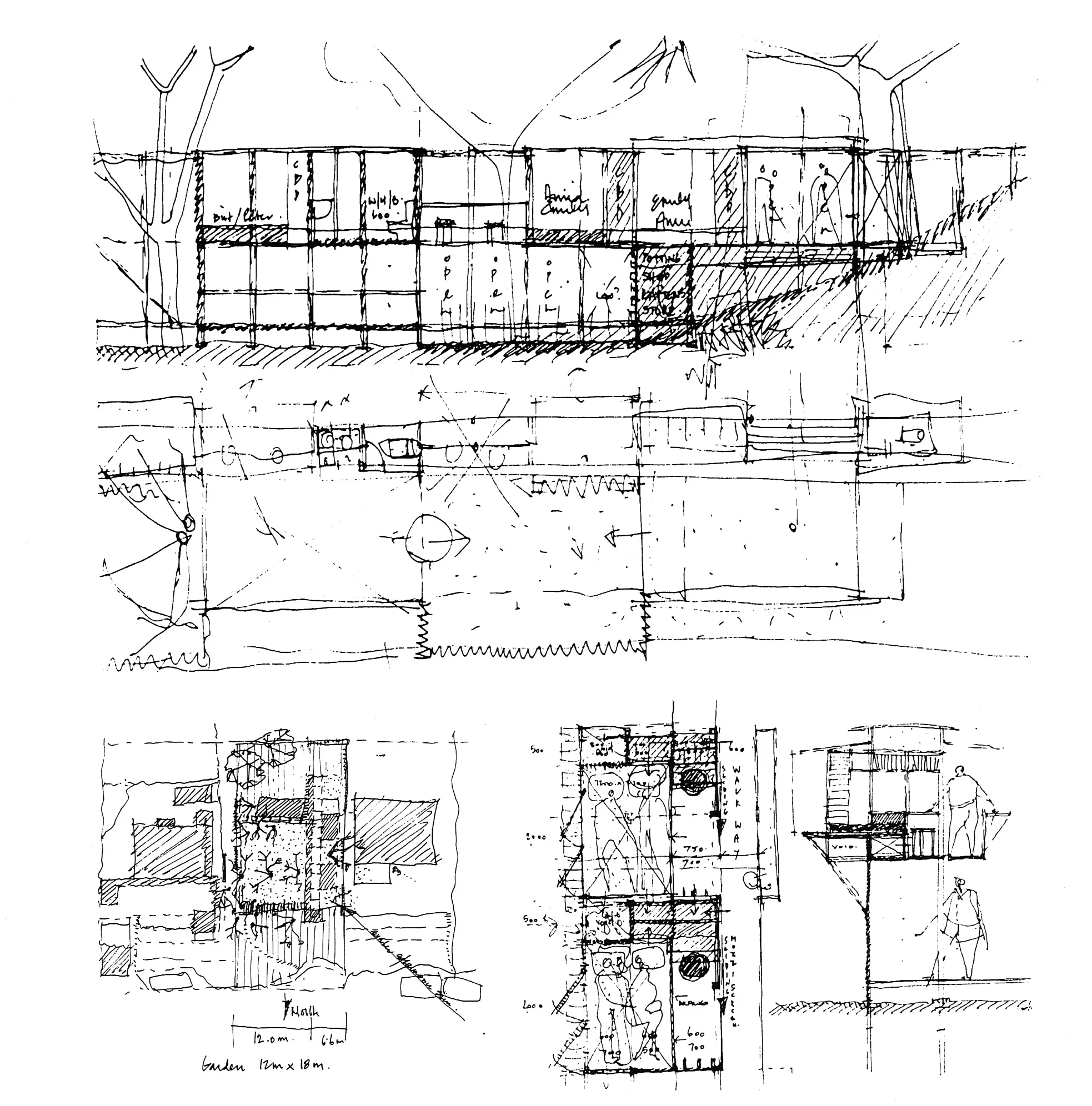

The intentions in the design of Mooloomba House include deferring to the existing landscape, alluding to a mythical landscape and creating a constructed landscape to intensify the place of the house in its wider setting.

Firstly in order to fix the location of the house in the surrounding landscape we sought to sustain coherence between the site and the greater landform. For example whilst the central courtyard is loosely bounded by a cloistered walkway the site enclosures have been ‘eroded’ in places to allow traces of the larger landform to be seen from within the site across neighbouring properties. The visual coherence of the sloping landform for instance is sustained by retaining the existing banksias grove and revealing the continuity of folding topography of the hill through the centre of the site and beyond its boundaries.

Secondly, the design explores the inclusion of mythical and metaphorical landscapes together with their small shelters such as the child’s tree house or the small bower in Paradise of the belvedere setting. The perched sleeping alcoves and the ‘lookout-nest’ of the north deck, invite reverie and are designed with recollected experiences in mind.

The third landscape is the ‘imaginary forest’ constructed, as one continuous landscape adjacent to the western boundary, through the two principal rooms and small courts. In this constructed landscape thirteen cypress columns have been set, off-grid, among growing tress and overhead interlaced in places with irregularly spaced rafters as a counter-point to the native forest of the banksia grove of the central courtyard.

Text edited from Architects' Statement, and drawings, from 'UME 22 - Andresen and O'Gorman Works 1995-2001' by Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper, 2011

Axonometric Drawings : Michael Barnett

Photos : Michael Wee, from '70/80/90 Iconic Australian Houses', by Karen McCartney published by Murdoch Books, 2011